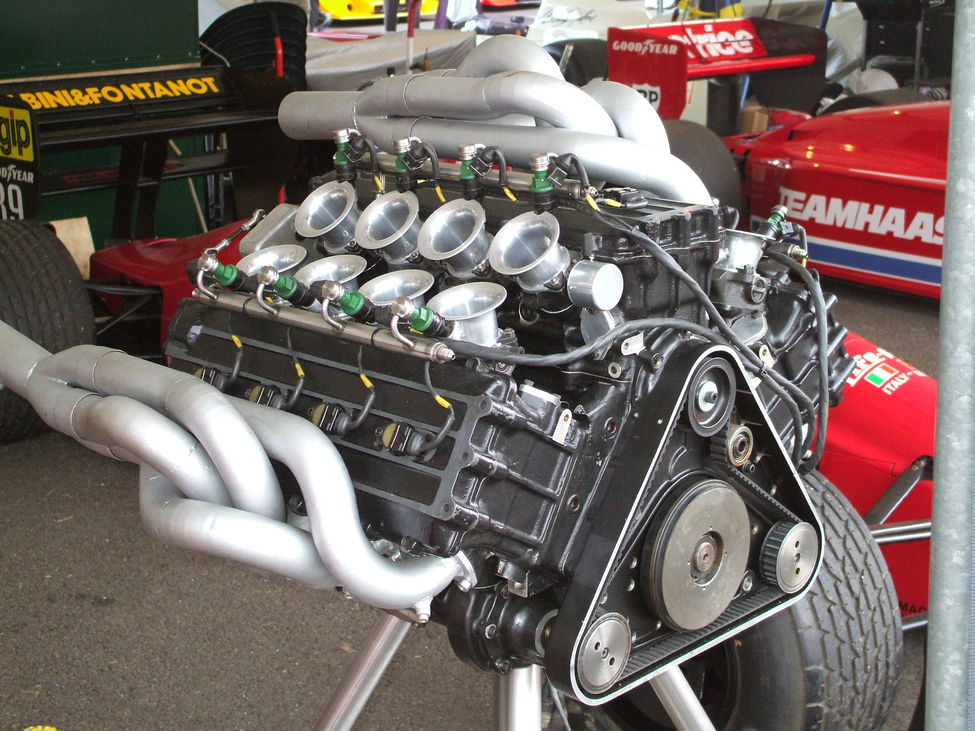

The story behind the Life F190 begins with Franco Rocchi, a long-time Ferrari veteran, who had a vision for a new type of engine: the W12.

It was a relatively simple idea, on paper. Rocchi, an engine man, died in the wool of Enzo's idea that the horse should pull the cart, wanted the power of a V12, but in the size and compactness of a V8.

To achieve this, he simply put the usual two blocks of four cylinders in the classic V-shape, and then crowbarred in a third block in-between.

The result? An engine he claimed he nearly 15kg lighter than the equivalent Cosworth offering, and the timing was perfect as F1 moved away from the turbo-charged beasts of the mid-1980s.

It was 1989, and the new rules meant naturally-aspirated engines were required but there was a split.

The likes of Honda, Renault, and Ford all went for a V10 design, but Ferrari being Ferrari opted for the brute of a V12. It was not until 1996 the Scuderia would ditch those extra two cylinders.

Rocchi had an engine but needed someone to bankroll its development, and ideally a team to run it.

Enter Ernesto Vita, an Italian businessman, who no doubt thought he had stumbled on the best 'get rich quick’ scheme he had ever seen.

The only problem was that no team was interested in this experimental engine, with no testing and shaky foundations. So, Vita did what any reasonable person in his position would do.

Created his own F1 team from scratch.

There were no FIA expression of interest processes and financial negotiations with the commercial rights holder (Bernie Ecclestone) to navigate.

The Birth of Life F1

In a further bid to get on quickly with things, Vita decided against building an in-house chassis, opting for to purchase one off the shelf from First Racing, an F3000 team which had made an abortive attempt to enter F1 for 1989.

Its first chassis had a major defect after being manufactured with a temperature defect in the autoclave, and running repairs made it overweight, with a second chassis being made up as a result.

It was this second chassis Vita snapped up. He had an engine, a chassis, but lacked one important ingredient: the squishy, organic bit in the middle, which would actually drive the car.

With a skeleton crew, Gary Brabham, the son of three-time world champion Sir Jack, was brought aboard, and after very limited testing, everything was shipped off to Phoenix for the 1990 season-opener.

With only 26 cars allowed to start any grand prix, and with regularly 35-40 on the entry list, the early 1990s featured 'pre-qualifying' on a Friday morning.

Essentially, the no-hopers were grouped in their own session to see who would advance through to 30-car qualifying for the 26 grid slots, with those who failed to pre-qualify earning a DNPQ on their record.

Brabham posted a 2:07.147 time, 5.7s slower than Claudio Langes in front and 35.8s slower than pole-sitter Gerhard Berger's eventual pole time, but remarkably, he was not the slowest as Bertrand Gachot's gearbox cried foul and gave up in his Coloni.

The comedy of errors had begun.

Brabham feared the team could fold before round two in Brazil, where he completed 400m before the engine failed. This was because the mechanics had gone on strike and not filled the engine with oil as they had not been paid.

The Australian pleaded with Vita to ditch the W12 and move to a Judd V8 design. By no means powerful, but reliable and trustworthy. Vita point-blank refused so Brabham left and went to F3000.

From bad to worse

In Brabham's tracks came Bruno Giacomelli, the veteran Italian who missed F1 and was deemed a safe pair of hands.

He returned from round three at Imola, where he recorded a lap-time of 7:16.212 in pre-qualifying.

This was because the oil and water pumps broke, leaving Giacomelli stuck in third gear for the crawl around the fast pre-1995 chicane-less Imola.

At Monaco, he even man-handled the car to within 14s of the fastest pre-qualifier and nearly 20s behind Ayrton Senna's pole lap.

The downfall

Vita then started to look for investors for his failing team, and in a stroke of the opposite of a masterstroke, looked to the Soviet Union.

The USSR was in a state of what could be termed as 'collapse' following the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, and so investment from behind the Iron Curtain was probably not that secure.

Predictably, it fell through and by round 13 in Portugal, Vita finally allowed the Judd V8 to be bolted in the back of the car.

It did not have the slightest effect whatsoever.

After Estoril and the Spanish GP at Jerez, Vita finally saw sense, and being gently nudged in the direction by Ecclestone, folded the team.

The early 1990s were a ripe breeding ground for the likes of Life.

Onyx, Andrea Moda, Coloni, AGS, EuroBrun to name a few.

Chancers, maybe; visionaries, certainly; dreamers, possibly. All in over their heads as if they were standing at the bottom of Challenger Deep in the Mariana Trench? Absolutely.

Also interesting:

Join RacingNews365's Ian Parkes, Sam Coop and Nick Golding, as they reflect on the first 14 rounds in this F1 summer break special! Red Bull's early driver change is looked back on, whilst calls from Bernie Ecclestone for Lewis Hamilton to retire are discussed.

Rather watch the podcast? Then click here!

Don't miss out on any of the Formula 1 action thanks to this handy 2026 F1 calendar that can be easily loaded into your smartphone or PC.

Download the calenderMost read

In this article

Join the conversation!